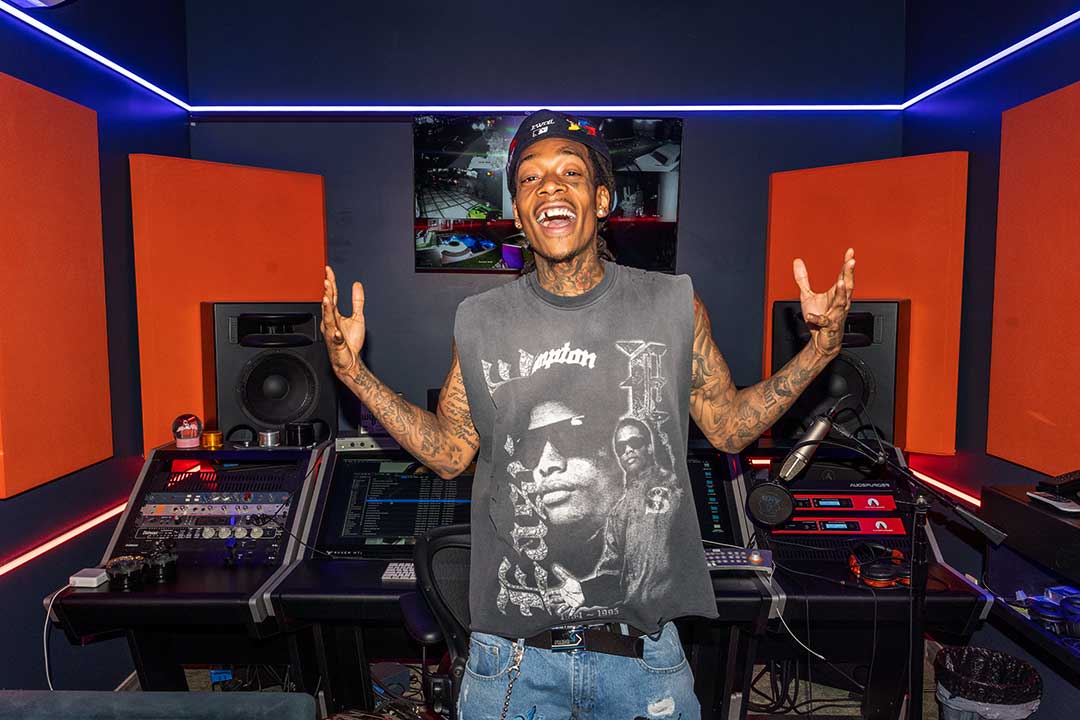

The name Carl Cox needs little introduction to dance music aficionados. A veteran of acid house and techno, he’s become one of the most celebrated DJs on the planet, nurturing the club scene with relentless enthusiasm.

A founding father of the emerging British rave scene, Cox’s F.A.C.T. mix CDs were hugely influential in the mid-’90s, followed by releases on his own Intec and Intec Digital labels, which seeded success for dozens more artists. However, his pioneering career has not been all plain sailing. Disillusioned by the process leading to the release of his 2011 album All Roads Lead To The Dancefloor, Cox swore it would be his last.

That all changed when he acquired a Pioneer DJM-V10 6-channel mixer, which allowed Cox to record and remodel stems culled from his hybrid live performances. Captivated by his improvised jams, his passion for music making was instantly renewed, leading to the swift release of his latest studio album Electronic Generations.

It’s been 11 years since your last album All Roads Lead To The Dancefloor. What were the reasons for such a lengthy recording break?

“When I made that album I was using other people’s studios, but I was never comfortable doing that because the sound, the environment or my head never seemed to be in the right place. I’d write a track and then I’d think to myself, what do I do next, breakbeat, acid, folk? I was fighting to make every single track and an album in its entirety.

“I stand behind everything I’ve done, but when I was sitting in a studio that wasn’t mine with two producers who I love dearly but had different ideas about how the music should come out, it was quite an arduous task because I wasn’t getting hands on with the gear. With All Roads Lead To The Dancefloor, I wore my heart on my sleeve and used a lot of vocalists, percussionist and guitarists from Melbourne.

“My only regret was that it was put out independently, so the time, money, ideas, concepts and marketing fell down to myself and Jon [Rundell] who was running Intec Records for me at the time. We had this clever idea to put the album out on a USB stick too, but it took a year to make and cost me a fortune.”

You took the album out live too. Did that go to plan?

“I said to myself that the only way to really sell the album was to go out live, so I did two live shows in Australia, which were really good, but gathering everybody together was like herding cats [laughs]. Going out as a DJ was a foregone conclusion, but going out as a live artist is another story completely – it was difficult to roll it out and sell it as a live album.

“When I signed to BMG 30 years ago, I went out as a live artist and had a really great time doing those shows, but it took a lot of time to put them together and DJ at the same time. It’s much easier to play live now, especially in terms of all the equipment you have to take out with you, but I got to the end of that album and said to myself, that’s it – I’m not doing any more. In the end, I built a studio just to do club tracks and remixes.”

What brought you back to recording music again?

“During the pandemic I turned the studio into a live streaming room. All the machines that you see here were in separates and I thought, I’ve got plenty of time on my hands so why don’t I just chuck all this stuff together and see what happens. I started experimenting – what if I buy that module or what will it sound like if I plug this into that drum machine? Instantly I was making music with no pressure whatsoever.

“After putting all the machines together, I was asked to do live streams for certain festivals that I couldn’t physically be at. Movement Detroit was the first one but I told them that I didn’t want to DJ; I wanted to play my machines and go live with music that nobody’s ever heard before. They said, sounds like a good idea and you’re Carl Cox, so why not? So I put all the gear together and did a few rehearsals behind closed doors.”

How did that process turn into what we hear on your new album, Electronic Generations?

“One of the reasons why this album came about is because I was using a Pioneer mixer called a DJM-V10. It came out just before the pandemic and after I’d used the beta version I told everyone that this mixer was going to be a game changer. People laughed at me because there are millions of mixers on the planet and I’d obviously got paid to say that, but I’d been working with Richie Hawtin’s Model 1 mixer, which is great, and there are a few things that it can’t do. One of those is recording live stems for each channel via MIDI.

“I thought to myself, if I’m running all of my machines through the V10’s 6-channel mixer and can record everything that I’m doing as stems, that’s a game changer because I’m jamming and rocking the hell out of these machines and adding certain elements to my music that I never would have thought of sitting in front of a computer. Once I’d done a mix, I could go back, remove the top and the tail of it and turn it into a track. That’s something I’d never done before.”

Did you have any technical problems recording the live sets?

“Sometimes the MIDI drops out, which makes things interesting. To be honest, you have to expect the unexpected. If it does fall over, great – it’s live, we’ll be back in a minute – does anyone know any songs? My fall back is that I have a second computer and a DJ setup if need be, so I can still provide a show. But there’s no pressure on the computer’s CPU whatsoever, so unless someone spills a beer on it I can more or less guarantee that we’ll get through a two or three-hour show.”

How inspiring was it to stumble on a new way to make tracks?

“Sitting in front of a computer with nothing going on and creating a bassline or a drum pattern is nice, but it’s just nice. When you’re playing live, there’s nothing nice about it – it’s coming out raw and you’re not thinking about anything other than what you’re creating at that particular moment. For me, jamming out my wildest techno fantasies and finding out what I could get out of these machines was really exciting.

“Even if it’s not making sense, you just stem everything out, take out what you don’t need and put in what’s missing. When you start working with these machines, after a while they start working for you. There’s a synergy and then the machines give you what you’re looking for and then some. I’d never have been able to sit there and programme any of it because I wouldn’t get any happy accidents. Thanks to the V10, this is the only way that I was able to come back and make an album, and now the whole studio makes more sense to me.”

Can you tell us about some of the machines used in your live setup?

“Equipment-wise, the Moog Subharmonicon is an amazing machine to have – although trying to control it is another story. I have a love/hate relationship with it. It’s such an amazing, powerful piece of kit that you have to try and capture those moments where its weird sharp keys end up. The sound moves around a lot, so you have to try and catch those oscillations because it’s hard to make sense of that while the pattern is being driven. On the one hand you’re fighting against the Subharmonicon, but it allows you to be more creative than you’ve ever been – it’s like a wild bull, but it’s responsible for a lot of the weird, spacey stuff on the album.

“The Moog DFAM (Drummer from Another Mother) is my go-to shuffle drum machine and is just brilliant, and I used a Korg Monologue on most of the tracks. A friend of mine told me that I needed to get one of them in the studio because it’s got some really good presets, you can write basslines on the fly and it’s small, so I bought the machine and thought, wow, it’s pretty powerful.

“The presets have a lot of really good analogue LFO movement and you can obviously manipulate those and do variances on the LFOs live. A lot of the top lines on the album are from that machine and it sits right at the front of my

live set.”

Is it true that you dusted some old gear down from your garage too?

“I had boxes of stuff that people had sent me – a TR-8 here and a Pioneer DJS-1000 there, so I was just pulling stuff out and hooking it up to see what it did. If I didn’t understand something I’d go online and look at tutorials. Most of the first part of the album comes from the DJS-1000 sampler. All I did was sit down and work on it for a week; then once I had a bunch of tracks I used it as a master controller and daisy-chained everything from there.

“I love hardware because software doesn’t translate live. For me, it’s not a live show until you can move, play and physically hit something – it’s the only way I can show that I‘ve gone from DJing to being a live recording artist that can perform live.”

How did the demo process take shape?

“I did another show for Mystery Man, one for our own label and certain shows for charity and I just found myself making all of this music – about four albums’ worth of mad tracks. Out of those live recordings I just sat down and, within a day, had about 18 tracks to work on. I demoed all the tracks and a couple of friends of mine told me send them to labels, but I didn’t think they’d be interested in someone who’s been around for eons making music out of all these machines because it’s not studio-based-sounding music and it’s not for the dancefloor, festival or clubs, it’s just raw electronic music coming out of these machines based on what I’d created.

“Thankfully, BMG’s Matt King decided to get back to me as soon as he heard it and said that’s exactly what we want to hear Mr Cox and we want you to sign a three album deal. I thought, if someone had told me that 30 years ago I’d be rich [laughs]. It’s unbelievable really because I’d always made music to suit the industry, but this album was the complete opposite; I was jamming my arse off for no other reason than having fun. They asked when I could finish the album off and I said, sometime next week – it’s done.”

Were the tracks really completed that quickly?

“The process of making the music was really quick, but the clever bit was getting the tracks to make sense. When you’re playing live, things come in on the threes, the ones and the twos – and some of the sounds were so improvised that a lot of the music is around the beats but not on it, so there was no real structure. When you work on a computer, everything’s so structured, but this music didn’t comply – sounds just came in when they felt right, but thanks to the process they at least had energy, soul, groove and power.”

The process sounds not so dissimilar to making house and techno tracks back in the day…

“Most of the acid house and techno music I was buying at the beginning was made on that basis. There was no Ableton Live or any of the amazing software we have now – there was no computer powerful enough to run those things. Back then it was like, woo, I’ve got a 4MB computer, this is great! You’d use a plugin and it would fall over.

“Most of what was recorded went onto a two-track tape and was spliced together and some of those records became seminal. Nobody could follow or copy those tracks because of how they were laid down. If you think of a track like Derrick May’s Strings Of Life, it was simple really, but genius at the same time.”

Once you’d sourced enough material for demos, how much more work did you need to do to turn them into fully-formed tracks?

“Not much at all. Each track that I jammed had its own element to it. When I moved away from the last track that I‘d jammed, I’d use a different module, drum machine or sample, so each track had its own flavour, whether that’s electro, hard techno, house, deep house or just electronica.

“The ebb and flow of the music was purely based on where I was going next. One track would be two minutes long and the next might be seven. I didn’t take any elements from one track and add it to another – that wouldn’t work because of the variation in key changes. Within each jam, there were obviously elements that might not have worked as well, but I’d either fix them or leave them as they were.”

Were you surprised at how gritty the record turned out?

“It did kind of surprise me in a way. If you listen to my F.A.C.T. albums, there are a lot of beautifully crafted trance records on there, like Cygnus X’s The Orange Theme, which is one of the most emotional records I’ve ever stood behind. I love that emotion and musicality because it’s not just attached to hard beats and the industrial sound.”

There’s 303 all over the record and that sound’s probably not as prevalent in dance music as it used to be. Do you feel it’s coming back into fashion?

“You’re right, but it’s one of those machines that’s always been associated with hard techno. I put it to the forefront because of my early days of acid house when you couldn’t play an acid record without it. We probably moved away from it because modern DJs never went to raves and haven’t heard the sound. Now when they hear it, they’re buzzing and sales of TB-303s are going through the roof.

“It doesn’t have to be a predominant sound, but it’s great as an embodiment of a low-end sound that can be put in-between basslines and percussion. For me, it harks back to the old-school days; it’s what got you off your feet. I’ve got the obligatory TR-8 drum machine, a TB-3 and it’s all running through MIDI, which is lovely. There’s no delay at all, it’s all running smack on time.”

How do you manipulate the 303?

“I manipulate the sound by putting patterns through a Moogerfooger then moving the frequencies around to make the 303 sound even bigger. By bolstering the sound and giving it a punk edge, I like to think that I’ve created a go-to Carl Cox 303 sound on two or three tracks on the album.”

You’ve also switched to Ableton as your main DAW…

“I only use Ableton Live. I’ve used Logic in the past, but found that I became quite rigid using that and the amount of parameters you have to go through becomes overbearing. Some people are geniuses on Logic, but I don’t have time for all that. Ableton wasn’t that great at the beginning from a sound processing point of view, so I’d just import all the files into Pro Tools, but I found that Pro Tools was going a bit too corporate so I switched back to Ableton and just got better and better at using it.”

Obviously, the process behind the making of this album was unintentional. Does knowing that your live shows are going to be committed to a recording suddenly introduce an element of pressure?

“I’ve got to think punk about all of this. They went in with an ‘I don’t give a shit, fuck you, bollocks’ kind of attitude. None of it was in key, they didn’t give a shit and didn’t even want to do it, but people loved it and they sold a million albums. How does that work [laughs]?

“For many years my music’s been accommodated: ‘Oh, that’s nice Carl, it’s a lovely track – I’m sure it’ll do well for you’, but with this album I really didn’t care. The rave scene was built on that energy – the whole jungle movement and breakbeat, The Prodigy’s Smack My Bitch Up wasn’t radio but boom, bang, and it’s a No 1 global tune. We need some of that to come back and it’s based on people’s attitude to making music.

“My music’s never really sat well with others. Even in the rave days I took it up to gabba, which is 180bpm. It wasn’t that I was angry or anything, but it was going somewhere until it wasn’t anymore. But my attitude was always punk – if I’m playing house, it’s the edge of house music, and the same with techno.”

There is a second version of the album on the way…

“The original album is literally Carl Cox’s Electronic Generations with 17 tracks and no guests, but I’m going to let them put out a reimagined version of those original tracks that allows certain artists to do something conceptual with the music. Fatboy Slim was the first and there are other tracks featuring Franky Wah, Nicole Moudaber, Juan Atkins, and Wilkinson. We’re nearly there with that, but it won’t come out until the original album’s been released.”

You have two studios, in Brighton and Australia?

“I built a fully-fledged professional recording studio in my old house in Horsham, which allowed me to do everything including mastering, but I never used it as much as I would have liked and felt uncomfortable recording at other people’s studios because it’s too stressful working against the clock. Eventually, I built a professional studio in Melbourne and when I walk in there now it feels like the best recording studio on the planet. Christopher Coe’s my right-hand man, an artist in his own right and a partner in my ASW label too.”

What speaker system are you using?

“As far as I’m concerned, my studio has the best speaker system in the world. I’m using Augspurgers speakers, which have incredible power and energy, and ADAM Audio S3X-H monitors that give a rich, low-end feel to the sound. What you can’t see is the Funktion-One sound system.

“We have these fucking great big mid-height TM monitors and on the floor is a big 24” sub bass cabinet. I’ll take my remote monitoring system, go to the back of the room and switch between the ADAMs and the Augspurgers, but when I want real world I’ll go to the Funktion-Ones, which sound unbelievable. It’s overkill, but if we hear any problems, I’ll rebalance the mix and boom - we’ve got it in the pocket!”

You sound totally enthused now…

“I’ve found myself in a very productive and creative place. For me, it’s necessary to go out there and show the people why I do what I do and if I didn’t love it we wouldn’t be having this conversation. This is my answer to entertaining the troops and the people who love electronic dance music. I’m excited to get back out there to my happy place – here’s a kick drum, we’re going to go somewhere from here and there’s no holding back!

“My DJ career is one great story but I think people know who I am as a DJ now and what I can do to any dancefloor. The live shows are unknown territory for me, but they’re also the tip of the iceberg because there’s a lot more to come. I could rest on my laurels as a DJ, but I still want to work for it and for people to understand that there’s no point companies making these machines and nobody using them. We’ve got plenty of DJs now; what we don’t have is a lot of electronic live artists that want to go out and perform, so hopefully I can be part of that new movement.”

Carl Cox's choice gear...

CCX Bus Compressor

“Made by the genius Arjan Hebly, it’s the hardest working piece of kit I own.”

Manley Massive Passive EQ

“A classic unit with such characterful EQ and power. It was this or two Pultecs...”

Zähl EQ 1

“Used on everything. For a master buss chain it gives us more air and better bass extension and clarity across the mix.”

Moog Mother-32

“Ah, the joy of this synth. Moog was so kind to give me this as a gift.”

Roland TR-8

“I use it all the time for my live shows.”

Make Noise Shared System

“I’ve had many sleepless nights trying to figure out the magic behind these amazing, weird boxes.”

SOMA Pulsar-23

“Joseph Capriati gave it to me for my birthday. I’ve never seen or heard a drum machine like it.”

Erica Synths LXR-02

“Proper techno comes out of this box as soon as you switch it on.”

Pioneer V10 Mixer

“My go-to mixer now; I can record the stems of my live show straight into Ableton.”

DOCtron IMC

“Master chain unit that I use on the final output of my live kit. An EQ, compressor and saturation box. It lifts everything.”